The challenge with talking about pricing (and especially multiple price points) is that the conversation comes in the middle of a much larger discussion on product design. By the time you've built a new feature and want to know how much more to charge for it (if you're even willing to adjust pricing), we're already three conversations into the dynamic.

Of course this is just my opinion. But I'm going to try to be clear and articulate about it because my buddy is going thru this very thing right now, and I love his product. So if anything I'm writing here helps you (and him), I'm thrilled.

Let's start the conversation someplace else.

Different versions of the product

Why are there 12 Hiltons in Chicago with prices ranging from mid $100/night to over $400/night? They're all good hotels, right? They all offer 4 walls, a floor & ceiling, a bed, and a bathroom, right?

Why does Mercedes make 7 SUVs that range from $36,000 to $76,000? They all offer roughly the same ability to drive from one point to another with at least 4 passengers in each one.

Why does Comcast xfinity offer four internet plans from $45/month to almost double ($85/month)? It's all just internet access. Why the four prices so I can check my email and browse the web?

If you're building a WordPress plugin, or a SaaS product that mostly delivers value on someone else's website, you can likely connect the dots. These three vendors are not offering completely different products for different prices. They're offering different versions of the same product, for different prices.

That's what you're looking to do too, right?

But how do you do that correctly? What's the logic or strategy associated with how you go about defining your price points and the tiers of your product offering?

Let's talk about (micro) segments & how they relate to price points

I like to use the term micro-segments because I'm still talking about roughly the same personas. But let's dig into what I'm really talking about when I use this term, especially as it relates to pricing.

Let's go back to the Hilton, the Mercedes, and xfinity.

Sometimes I travel to Chicago for business. When I'm there for work, I am there for meetings – which means I don't want to go looking for places to eat (before or after walking to my appointments). So I want a hotel in close proximity to whatever office I'm visiting, and I want a restaurant in the building. I prefer breakfast to be included.

Other times I travel to Chicago for pleasure. When I bring my family to town, to see a show, to visit a museum, or to watch beach volleyball, I want a hotel that has a pool and a hot tub, has suites, great beds, and close proximity to restaurants.

I'm one person. But I function in two different capacities depending on my goals. And the number of times I visit as a corporate person is several a year. The personal visits may end up only being once every two or three years.

What does that mean?

It likely means that along with my needs and desires, my sense of fair value also adjusts. And I'm not even getting into the complexity that in one role I'm likely to expense it while in another role, I'm paying out of pocket.

So let's break out a few of the many micro-segments that look for a hotel in Chicago:

- Solo business person, close to offices, breakfast included

- Solo business person, needing suite to host meetings

- Corporate team of people, close to offices, need meeting room

- Individual, tourist, close to restaurants

- Family, tourists, close to restaurants – need two beds

- Family, tourists, price-conscious, need suite for family of 4+

These aren't the only ones out there. But you can see that they each have different needs. I use a framework for this called a goal pyramid, but you can see, I can just present it in a bulleted list just as well.

These are the needs that later drive our offers (which may require new features).

I could take you into the same dynamics for buying a car, or choosing an internet speed. But it all comes down to the same thing.

When I buy internet, I buy it differently if I'm just using it for email and I'm a college student, than if I'm a tech guy who works remotely with a ton of video calls, than if I'm part of a family with teens who will stream all weekend.

The needs and goals I have will drive the features I need, which will dictate the value I get, which drives what I'm willing to pay.

So how do we design features? What drives the decision?

If you've heard me speak in the last few years, there's a chance you already know the answer to these questions. It's my opinion. (But I shouldn't have to say that – everything on this blog is my opinion.) But I hold it strongly.

I am of the opinion that once you get a good set of features to deliver value to one micro-segment, you shouldn't spend time and money adding features for them. You should, instead, focus on adding more features that broaden your appeal.

In other words, there was a time when xfinity offered 1 plan. Then 2 and then 3. And there was a time when Mercedes had 1 SUV. Then 2, then 3. And Hilton didn't magically have 12 hotels in Chicago all at once. They added more (or bought more).

Let me be even more explicit.

What I'm saying is that if you're working on a feature right now that doesn't open up your available market to new micro-segments, you'll likely not going to see the same return on that feature as you will if you create features that drive growth along new segment lines.

The best part of building a feature that focuses on a micro-segment is that it comes with a compelling story already baked in (which you know I love).

When you look at less expensive SUVs (regardless of who makes them), you may notice that their performance (speed, horsepower) is lower. But you may also notice that their security features are less.

Now, if you're me, I like faster cars. But my wife is all about the security features that come with her SUV. I'm talking about the automatic and intelligent breaking, lane assist, and more.

Those features tap into a different segment of the market that allows them to craft the pitch about protecting our “precious cargo.” The story is just there waiting to be used.

(And now you know that I own one of the more expensive SUVs because my wife is the boss around here.)

This is why product ladders are so critical

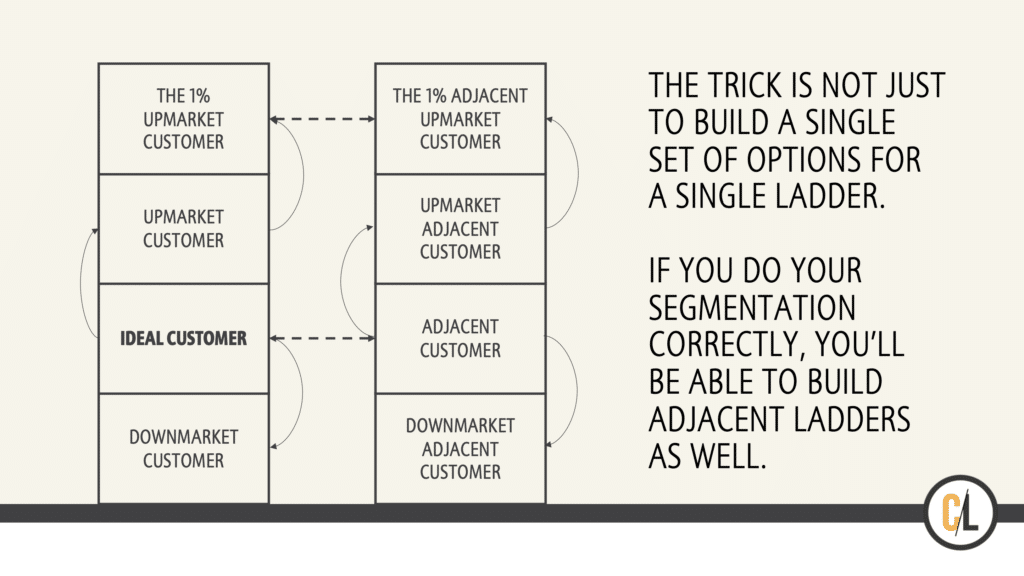

Normally, when I'm talking about product design (and multiple price points), we'll start talking about product ladders. It's about crafting offers (variations) of your product that connect and deliver value to your different micro-segments. (Remember that your product and your offer aren't the same thing.)

When you are clear on who your initial idea customer is, you realize you've built the product for them. But what about that downmarket customer who needs less and wants to pay less? Where's the product variation for them?

What about your upmarket customer? What if they want more? And are willing to pay more?

And don't forget that your product may be great for adjacent markets. Especially if you subscribe to the “create features that open up adjacent markets” concept I raised above.

When you start crafting these variations (because you're adding key features to expand the allure of your product to adjacent markets), at various prices, you'll see growth.

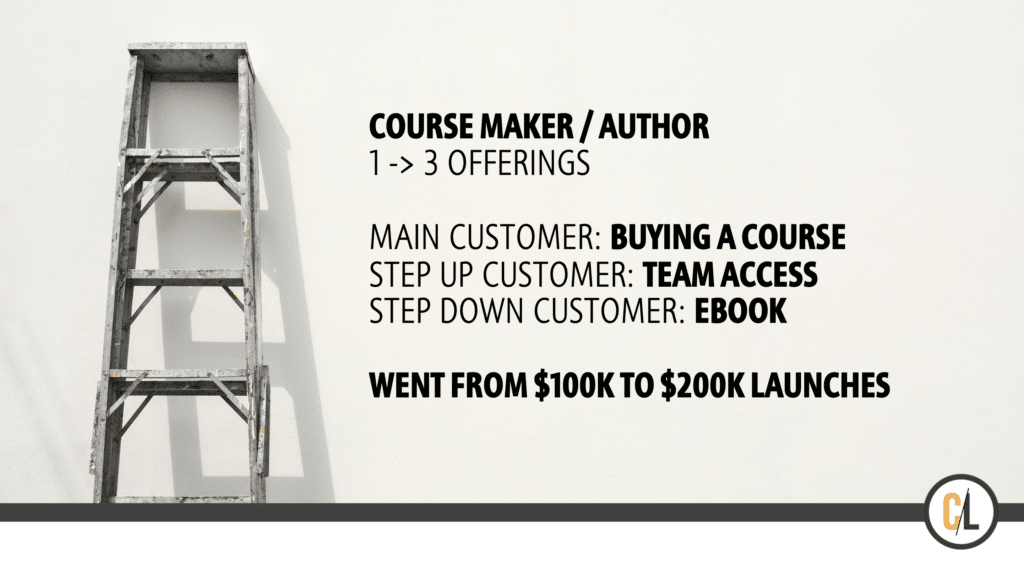

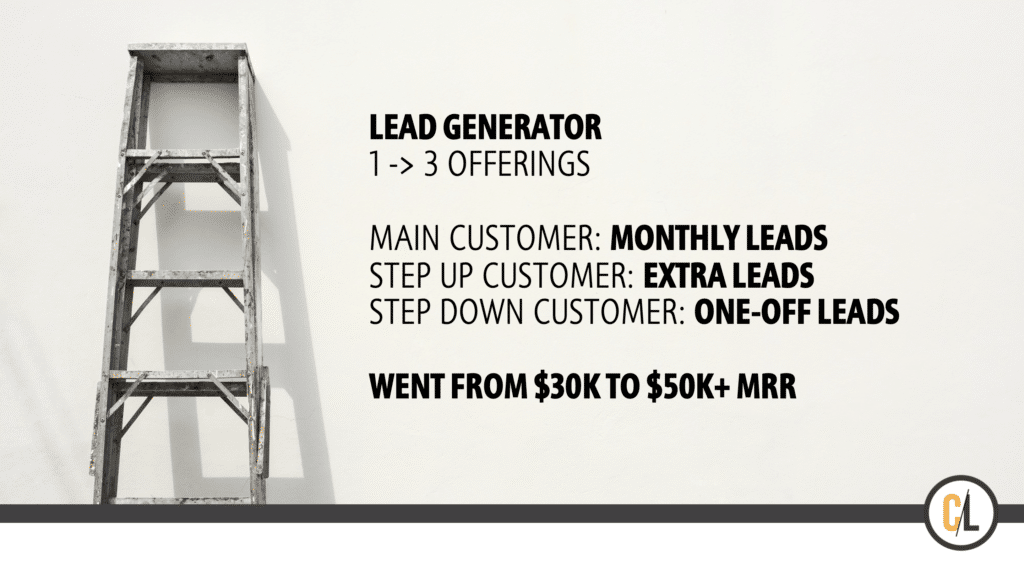

Here are the results from two friends who I've helped work on this strategy with.

The beautiful thing about each of these stories is that they were able to say “yes” to a lot more customers while also driving revenue way up.

Building multiple price points

Remember when I said that the conversation around pricing, for features, is three conversations into the mix. Well, now you see what I was talking about. Here are the three conversations I'm talking about:

- We talk about your micro-segments and their goals (goal pyramid).

- We talk about the offers that help different segments (our product ladder).

- We talk about what features we may need for these offers. (offer design)

- We talk about the value delivered to each segment. (define pricing)

You'll notice in the third conversation I said “we may need.” Not every new offering requires a new feature.

I worked with one client who simply added a sort-order to their ticketing system so that customers with a special tag had their tickets moved to the top of the list. The offer was the ability to buy the tag and get it applied to your account.

Immediately they have multiple price points for their products. The price for the regular product. And the price for the product with the enhanced / escalated support. And they were able to do that without coding / developing any new features.

As you can now see, my strategy for building multiple price points this way comes from the outside in. We start with the customer, their goals, the features we can create, and then, lastly, the price.

Most people go inside out. They start by building a feature. And then they figure out how to present it on their pricing grid and how much to charge for it.

I've talked about this before.

It starts with that target customer

If I were building a SaaS like Damon, I wouldn't define my pricing grid as “Starter,” “Premium,” and “Ultimate.” I'm not picking on Damon. I'm simply stating that it feels very inside out, instead of outside in.

I'd start with my segments.

Sure, the first plan could easily be called “Free” but after that, I'd focus on the segments that will automatically self-select when they see their profile in the title.

Is he focused on freelancers, agencies, or SaaS companies, or enterprises? Some of them? All of them? And if he is, I might suggest defining the plans with those names.

More importantly, I would use my goal pyramid and product ladder work to define the left column of features.

What I'm looking for is where these different segments differ. Remember when I'm traveling to Chicago for work, I don't care about a pool. I do care about breakfast included.

The more clearly I can distinguish the segments and their goals, the better I can create pricing plans that feel almost obvious to the customer. After all, if I include an enterprise-level feature only in the last plan, no one stresses about it. (They don't need or want those integrations.)

Hopefully this helps you think about things. You can always book time with me on Clarity.